UMBC LSAMP

To help facilitate the campus community transition to remote learning, the UMBC LSAMP program remains available to meet with STEM students. To set-up, a meeting to discuss your academic and professional interests, send an e-mail to lsamp@umbc.edu.

We will house resources to support students in their adjustment to remote learning below. Underneath the presented resources, you will find links to additional resources and our mission statement.

References: Kwantlen Polytechnic University Learning Centres, Christina Page, Adam Vincent, and the University of Florida

Helpful Resources Identified by UMBC Office of International Students and Scholars (OISS)

Please select review the Office of International Students and Scholars’ website more information:

- Sources of Good Information

- Preparations

- Protecting Yourself

- Health Insurance Information

- Discrimination, Stress, and Anxiety

Critical Questioning to Support Your Learning

Learning in an online environment requires you to move beyond simple memorization of course concepts. To gain knowledge that will support you in your growth as a lifelong learner and in your future career, you will want to interact with course concepts deeply and in ways that are personally relevant to you.

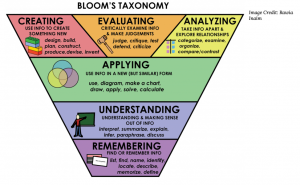

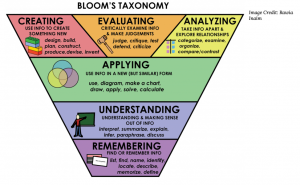

One way of picturing deeper learning is Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The levels of Bloom’s taxonomy build upon each other. While you need to be able to remember key concepts, your courses will spend more time developing your ability to apply, analyze, evaluate, and create using this knowledge. As you encounter new concepts, you will want to use critical questioning to understand the concepts at all levels, moving from surface to deeper knowledge.

The following printable chart includes some questions that might be relevant at each level: Bloom’s Cognitive Chart

We’ll get through this together. Things may feel out-of-control right now.

You may be facing a lot of unknowns and disruptions. Try to be patient with yourself, your classmates, and your instructors during this time. Take care of your wellbeing first. Making a plan and adjusting your studying may help you feel even a little sense of control.

In this guide, we’ll talk about:

- Staying organized

- Avoiding multitasking

- Making the most of video lectures

- Setting a schedule

- Trading your strategies for new ones

- Working with a group or team

- Staying connected to other people

Your study habits may need to change.

The full guide can be found at Tips for Academic Success during COVID-19

Guiding Family and Friends through your Remote Learning Experience

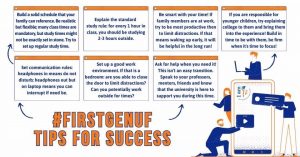

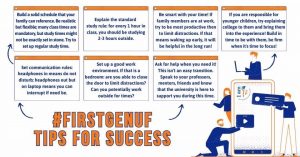

The University of Florida created a visual resource supporting first-gen students transitioning online!

Assignment Planner

The idea of completing a major research paper may seem overwhelming, but if you can divide the task into achievable steps you will be on your way to success. Use the chart below to break your assignment into smaller steps. You will want to create steps that can be done easily in one day, and preferably in a single work period. Consider the following example breakdown for a research paper.

| Assignment Task |

Target Completion Date |

Complete? |

| Read assignment instructions and rubric |

March 23 |

Y |

| Review course materials and choose the topic |

March 24 |

Y |

| Library research — find 3 peer-reviewed articles and two books |

March 25 |

N |

| Read and take notes on two articles |

March 27 |

N |

| Read and takes notes on the final article and books |

March 28 |

N |

| Organize notes; write thesis and outline |

March 29 |

N |

| Write body paragraph 1 |

March 30 |

N |

| Write body paragraph 2 |

March 30 |

N |

| Write conclusion |

April 2 |

N |

| Write introduction |

April 2 |

N |

| Self-edit content and organization (use the rubric) |

April 4 |

N |

| Writing tutor appointment |

April 5 |

N |

| Edit and proofread assignment |

April 6 |

N |

| Submit final assignment |

April 8 |

N |

In the above example, the assignment is divided into smaller pieces, with a manageable amount to complete each day. It is also clear when each task has been completed. A daily work goal like “work on the research paper” is not well-defined, and can seem overwhelming. This can make it easy to procrastinate. By choosing specific and achievable goals, you may become more motivated to get started, and you will be able to measure your progress each day. Remember to reward yourself for meeting your goals along the way.

Find a printable worksheet at Assignment Planner Worksheet

WOOP Goals

A lot of people are familiar with SMART goal setting: setting goals that are specific, measurable, action-oriented & achievable, realistic, and time-oriented.

If the SMART framework helps you in your process, fantastic. If, however, SMART goal setting has never quite clicked for you, or if you’re super familiar with SMART goals and want to try something new, consider using the WOOP process, developed by psychologist and researcher Gabriele Oettingen, whose work explores the ways that we think and how this impacts our behaviors.

What’s WOOP all about? Here’s what it stands for:

- W – wish

- O – (best) outcome

- O – (main inner) obstacle

- P – plan

How’s it work? Like this:

To get started, think about a wish that you have for yourself – something you want to make happen. It should be both challenging and feasible: maybe it makes your heart beat a little faster, but you can do it.

It’s important in this WOOP scenario that the wish be something important to you. It needs to matter and mean something to you, rather than being a wish that somebody else thinks you should have or wishes for you.

Now close your eyes (seriously, close them, or go in a dark room, or lie back and put your arm over your face…) and imagine what it will be like to have this wish come true. How will it look? What will it feel like? What will you do when it happens? Where will you be? Who will celebrate with you? What will it mean? Imagine all of it, visualize it to the greatest detail you can muster, make it actually happen in your mind. Then, return to wherever you are in real life and jot some of these imaginings and visualizations down.

Next, imagine and visualize what your biggest obstacle will be. WOOP is specific in stating that this should be an internal obstacle – something that will come up inside of you that could derail you from your wishing and throw you off your success path. Maybe it’s something you notice you do, something that distracts you from whatever it is you need to be doing. Or maybe it’s that you notice your self-talk isn’t kind or supportive. Maybe you have a hard time juggling everything you need to do — for yourself and for others. Maybe it’s something else entirely. Whatever it is though, identify it.

Once you’ve imagined the greatness of success and the possible barriers that could get in your way, it’s time to plan. Planning is huge, no matter how you choose to set goals. In WOOP, the planning has to do with what you’ll do to overcome or navigate that obstacle inside yourself when you encounter it. If you know that you like to sit down and watch a show on Netflix, and then all of a sudden it’s three hours later and you’ve binge-watched half the season, what will you do when you notice yourself engaging in this Netflix feast? Maybe it’s that you’ll turn it off, no matter where you are, and tackle a piece of the wish you want to fulfill. Maybe it’s that you’ll look at your schedule, to remind yourself what you’re supposed to be doing. Or maybe it’s that you’ll make a schedule, so you know when you’re committed to your wish-fulfillment process, and when you’re committed to the rest of your life and its commitments, too. Think of it along the lines if-then. If this happens, then I’ll do this to course-correct/motivate/re-focus, etc.

In addition to this obstacle planning, think about your overall planning, too:

- When will you work on your wish or goal?

- What will your due-dates be for yourself?

- Who do you need to connect with?

- What material do you need to produce, and by when and in what form?

- Who will you connect with when it starts to feel hard?

- Who or how will you motivate yourself?

- What will you do to hold yourself accountable?

- When will you take time to pause and reflect, take stock of your progress, and assess your steps forward?

Regardless of the type of goal or focus, goal setting can be a useful tool for your time in college and beyond. It can help you see where you want to go, commit to a plan to reaching that place, and get there.

Find a printable worksheet to create your own goals at WOOP Goals

Staying Motivated and Proactive

1. “I Don’t Feel Like Doing It!”

Lack of motivation is a commonly given reason for not attending to an unpleasant task. Most procrastinators believe that something is wrong with them if they do not feel motivated to begin a task. This simply is not true. How many folks do you imagine feel motivated and energized by the prospect of raking leaves, or changing the oil in the car, or doing taxes? These tasks are often seen as unpleasant and less than exciting. To believe that you must feel motivated in order to begin a task has the order of events in reverse. In The Feeling Good Handbook, Burns (1989) writes that the “doing” comes first, and then the motivation. Thus, starting a task is the real motivator, rather than, motivation needing to be present prior to beginning the task. Often just taking the first step, regardless of how small, can serve as an inducement and thus a motivator for further action.

Another strategy involves taking an attitude check. Ask yourself: “Does my attitude prevent me from being motivated?” If your answer is “yes”, then it is time to figure a way to make an attitude adjustment. This may mean giving up on the idea that “everything in life must be interesting” or that “I have to like all my classes for them to be worthwhile.” It may also mean re-evaluating your goals and determining the “steps” which do or do not fit into the larger picture. If succeeding in the boring class seems to be a necessary “step” to achieving your larger goals, that fact alone may motivate you.

2. “But, I Don’t Know How?”

Skill deficits are one of the most basic reasons for procrastination. If you lack the skills to complete certain tasks, it is only natural to avoid doing them. For example, you may be a slow reader. If you have several lengthy articles to read before you can write a paper, you may postpone the reading because it is difficult. You may even have trouble admitting your poor reading skills because you do not want to be seen as seem “dumb.” Thus procrastinating may seem better than facing your need to improve your reading skills.

The key to solving skill problems is to identify what the problems are. Often a counselor, an instructor, or another professional can help you to make this determination. When you know the problem, then you can take action to correct it.

3. “But, What if I Can’t Cut it?”

Fear of failure is another reason people procrastinate. It goes something like this: If I really try hard and fail, that is worse than if I don’t try and end up failing. In the former case, I gave it my best and failed. In the latter, because I really did not try, I truly did not fail. For example, you may postpone studying for a major test and then pull an “all-nighter.” The resulting grade may be poor or mediocre, but you can say, “I could have done better if I had had more time to study.”

Similarly, you may delay researching and writing papers until the last minute, turning papers in late or incomplete. You then can also say, “I know I could have gotten a better grade on that paper if I had had more time.”

The payoff for procrastinating is protecting ourselves from the possibility of perceived “real” failure. As long as you do not put 100% effort into your work, you will not find out what your true capabilities are.

Another variation on this theme is that you may often fill your schedule with busy-work so that you have a “legitimate” reason for not getting around to more important tasks.

Perfectionism often underlies the fear of failure. Family expectations and standards set by parents may be so high that no one could actually live up to them. Thus, procrastination steps in to derail parental expectations and standards and prevent you from “really” failing.

Consider that the problem is actually the unrealistic standards that have been set, not your failure to meet them. The problem, and thus the “failure,” maybe that you begin to believe that you are not a worthy human being. You may procrastinate to such an extent from fear of failure, that you are actually paralyzed. Thus, you do not complete the task and achieve a more realistic level of success.

“Fear of success” can be the other side of “fear of failure.” Here you procrastinate because you are fearful of the consequences of your achievements. Maybe you fear that if you do well, then next time, even more, will be expected of you. Or, perhaps, succeeding may place you in the spotlight when you prefer the background.

Procrastination of this kind may indicate an internal identity conflict. If your self- worth is tied to your level of achievement, then you may constantly question yourself about how much you must do to be “good enough.” Each success only sets you up for the next bigger challenge. If your self- worth is tied to family acceptance, then how much more does it take for them to be satisfied? Each success only opens the door to greater expectations. Often this leads to a feeling of losing your identity and perhaps no longer being able to claim your successes as your own. Inaction or procrastination maybe how you cope with the pressures you feel to constantly try to be “good enough.”

5. “This Stuff Is Just Plain Boring!”

Lack of interest seems to play a role in procrastination. All students from time to time lack interest in a course, however, not all of these students delay in studying or completing assignments.

If your natural interests are not stimulated by the course content, one solution to procrastinating may be to “just do it” (i.e., simply continue to attend class and do the assigned work on time). This will give you more “guilt-free” time to do those things that are more interesting to you. Of course, it won’t necessarily make the class or assignment interesting, but at least you will not cloud the “good times” with worry.

Rebellion and resistance constitute the final set of issues which can underlie procrastinating behavior. Delaying tactics can be a form of rebellion against imposed schedules, standards, and expectations. The expectations are often those of a power struggle, usually not on a conscious level. As an example, your father has an accounting business and has always planned on having you become his partner after college. You are enrolled in the College of Business and like accounting, but since you started college you have been wanting to explore some other careers unrelated to business. Your father says, “No, you’ll stick to accounting and like it.” As a result, you don’t turn in work on time, “forget” to do assignments and earn low grades, sometimes flunking a course.

Rebellion against external evaluation is another facet of this sort of procrastination. For example, if a teacher has offended or angered you in some way, you may retaliate by turning something in late or procrastinating indefinitely. Sometimes these same tactics are used on classmates in a group project setting or with parents. The thing to remember is that you ultimately lose (i.e., getting the bad grade, loss of self-respect, etc.).

Rebellion and resistance are re-actions, not actions, thus, the control of your behavior rests with whatever or whomever you are rebelling or resisting. If you are rebelling against your parents, then they have a great deal of power in your life–probably more than you really want. Decide what you want for your life–don’t just react to someone else’s decisions for your life.

Adapted from Burns, D. (1993) Ten Days Of Self Esteem. New York: Quill.

Brought to you by

The Learning Corner @ Oregon State University | © 2017 success.oregonstate.edu/learning

Find a printable worksheet to create your own plan at Procrastination Awareness Plan and Procrastination Management Worksheet

Zoom Etiquette

Helpful Hints for a Successful ZOOM Meeting

- Check your technology ahead of time. Be sure to check the microphone and speakers to ensure they are working.

- Join the meeting from a quiet/ private workspace (private room or office space). If you cannot ensure a quiet workspace and must use a shared space (e.g. coffee shop, group study room, etc.) make sure you have a headset (earplugs/ headphones/ AirPods) that allows you to listen in privately if possible.

- Dress appropriately. Make sure you are joining in virtually like you would if you were attending the class in person. Your professors and peers can see you via video web/laptop cam or phone camera.

- Limit distractions where possible. In line with #2, if you can limit your distractions (TV, social media, etc.) while in a Zoom appointment, please do what you can to limit these things so you can remain engaged and focused in the meeting.

- Mute your microphone when you’re not speaking. This helps to reduce any ambient feedback/ noise from your microphone to help ensure a clear video call. You can use the spacebar to “temporarily” unmute if you’re on a laptop or desktop computer.

- Look directly into your web/ laptop cam or phone camera when it’s your turn to speak/ ask questions. This helps your instructor and/or classmates feel you’re directly talking to them.

- Use the chat function for questions during your lecture/ video call. If chat is enabled/ allowed in your video call, use the chat function to ask questions and/or help answer another student’s question. This allows you to ask the question without interrupting the speaker directly. You can also “privately” chat someone in the video Zoom call as well.

Students: Tips for Participation in Synchronous Sessions (e.g., Zoom)

- Make sure to pay attention, not being physically in class can be distracting.

- Email the professor if you have ANY questions/Communicate Often

- Participate in chats/discussion boards frequently

- Break out of your comfort zone and don’t let the physical distance be a barrier. Be even more open with your communication than you would be in person

- Don’t lock yourself in a learning vacuum: participate, communicate, and collaborate.

- If you are taking a synchronous class, suggest to your teacher the possibility of recording lectures so students can refer to it again later.

- Find a fidget toy, or even a mindless app on your phone (pattern matching, color by numbers, etc…) to avoid distraction.

- Make sure you have a place with stable internet connections to work in, and one that will not distract you.

- If synchronous-don’t forget your computer charger!

- Log in early in case you experience technical issues

- Talk/socialize with your classmates beforehand

- Chat often but not so much that it’s distracting

- Pay attention and take notes.

- Don’t be afraid to ask your instructor for help/clarification if you are confused about an assignment

- Make sure that you know of alternative places that offer access and accommodations for class time.

- Frequently check the channels of communication established for your course (Moodle/Blackboard; email; etc.)

- Simulate being in a real classroom, break yourself off from distractions. Having class on your couch at home may seem like a good idea but maybe set yourself up in an office instead.

- Snacks help keep you awake!

- Get Engaged! Inside and Outside of class try to participate which will enhance the experience.

- Let your instructor know about any limitations (lack of technology, disability, etc.) so that they can accommodate that for online lessons

- Know important phone numbers/emails in case you experience technical difficulties

- Make the learning environment work for you–move around, stand up and stretch, snack, whatever you need to make sure you stay focused and comfortable

- Make a friend to communicate with about assignments or vent to. If you work well together, try partnering up for collaborative assignments.

- If you’re kicked out of class by your technology, don’t stress out; it happens to everyone at some point. Just log back in.

References: Kwantlen Polytechnic University Learning Centres, Christina Page, Adam Vincent, and Oregon State University

UMBC Academic Success Center Services

Academic Advocates work collaboratively across the campus community, in partnership with the Academic Care Team, to assist students in resolving academic and institutional challenges that may adversely affect persistence, progression, and timely completion of a degree. No matter how complex the concerns (i.e., personal, academic, or financial), Academic Advocates will work together with students to review their progress, present options towards graduation, map out a plan for success and facilitate communication and connections with the appropriate campus resources.

Student referrals may come from a variety of sources including the individual student seeking support.

For additional information on the Academic Advocates, see https://academicadvocacy.umbc.edu/

For additional academic learning resources available through campus, seehttps://lrc.umbc.edu/